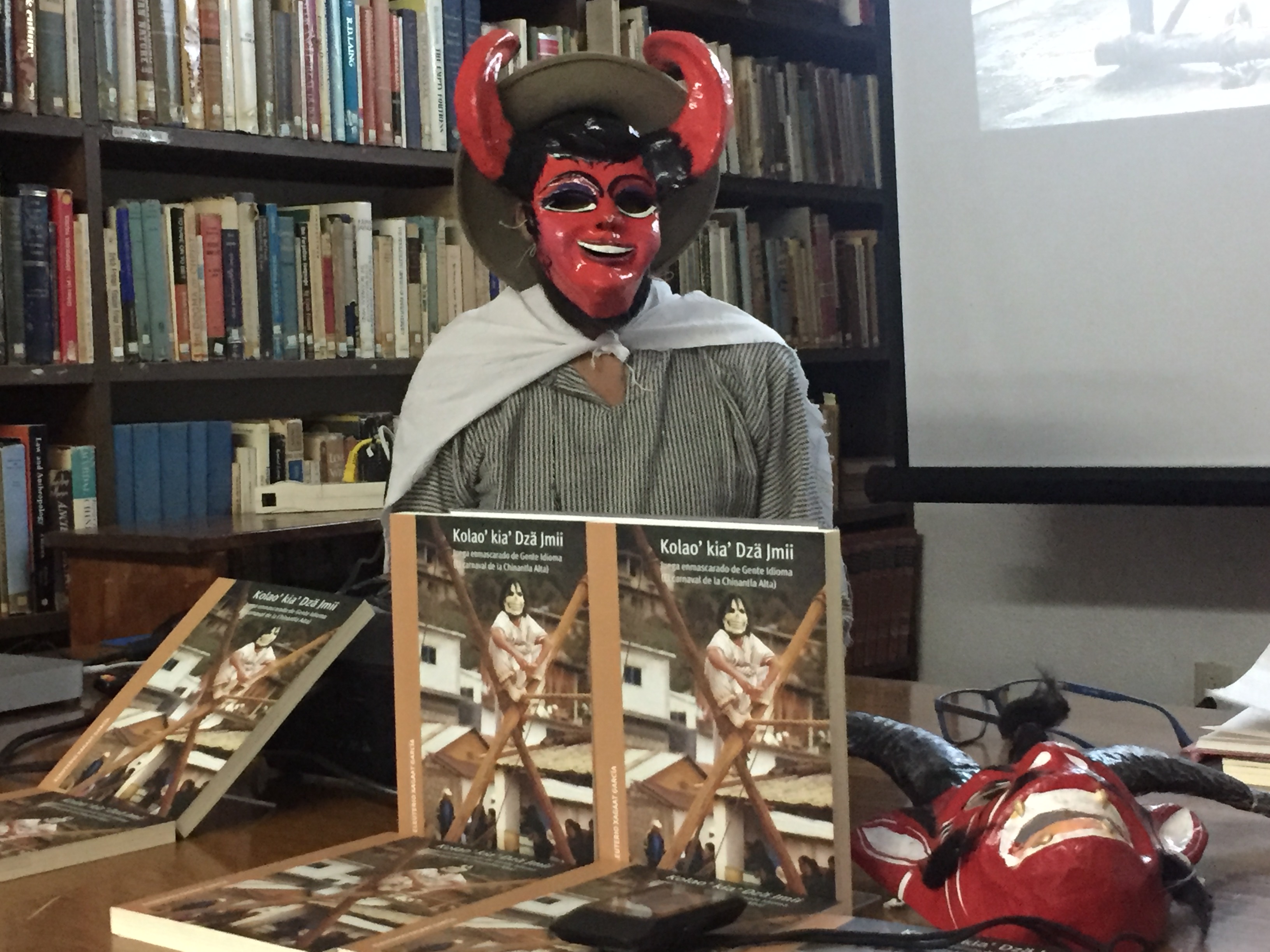

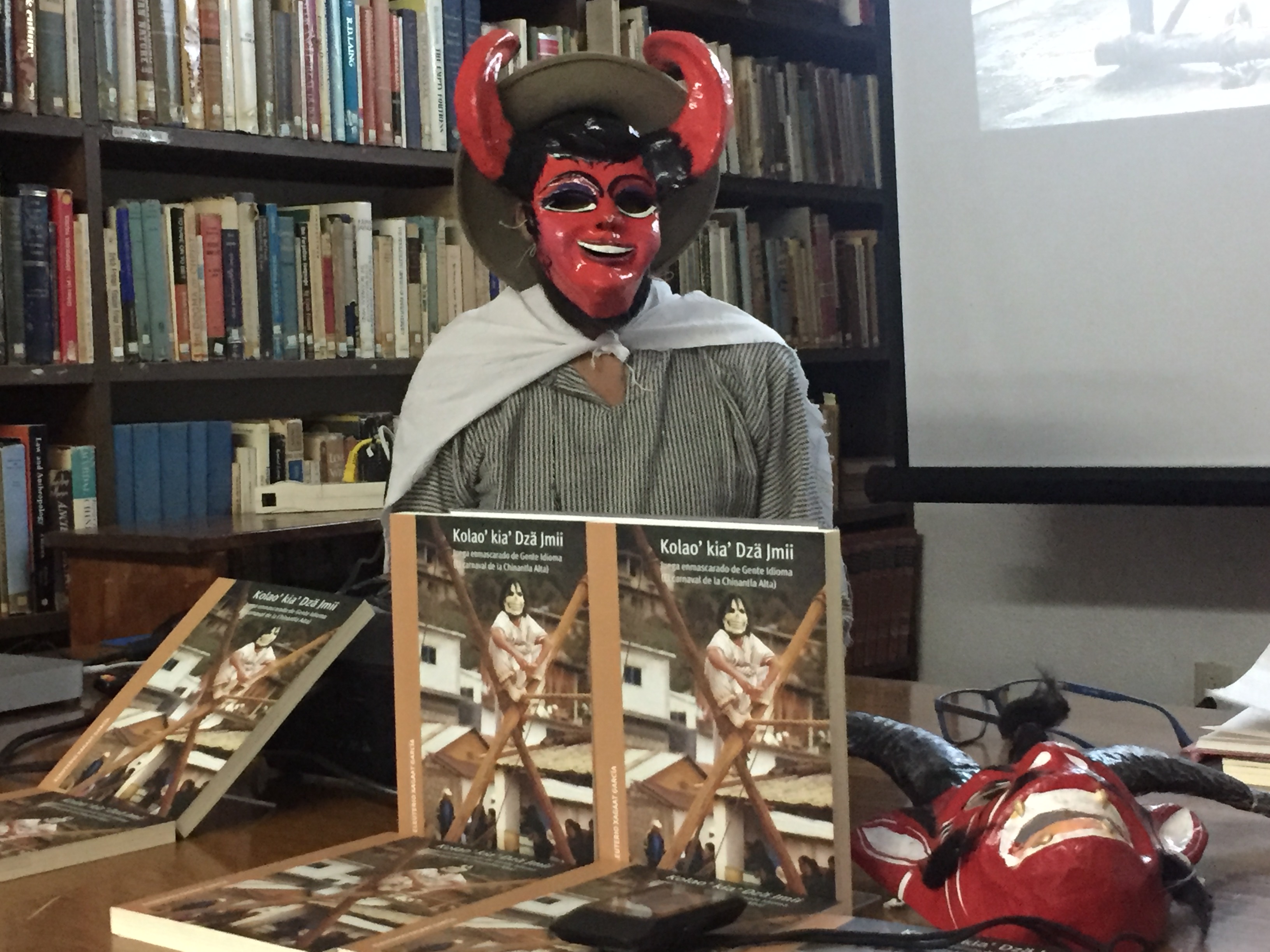

Comentarios sobre Kolao´ Kiá Dzä Jmii. Juega enmascarado de Gente Idioma (El Carnaval de la Chinantla Alta) por Eleuterio Xagaat García (presentado en

el INSTITUTO WELTE PARA ESTUDIOS OAXAQUEÑOS, A.C. 9 Feb 2018.

Vienen gentes extrañas… (6) y vienen a denunciar a las autoridades civiles y religiosas de las comunidades de Comaltepec, Yolox y Temextitlán. Este trabajo bilingüe chinanteco-español presenta descripciones de los ritos de Carnaval en tres comunidades de la Chinantla Alta del estado de Oaxaca, México, según la observación, la participación, el análisis y la fotografía del autor, Eleuterio Xaagat García, entre los años de 2006 al 2010.

Se ve la localización de las comunidades en este mapa, que por cierto es de gentes extrañas—el Instituto Lingüístico del Verano, pero en el mapa no se aprecia la geografía de la zona, casi en la cumbre de la Sierra Madre Oriental.

Presento aquí una perspectiva informada por mi posicionamiento como antropóloga, como extranjera, y como mujer, con comentarios que plantean mas preguntas que respuestas, en la espera de generar una conversación mas larga.

Como antropóloga, veo al Carnaval como un rito de rebelión en el cual los participantes cuestionan a las autoridades, y crean un espacio en el cual todas las normas se rompen (Gluckman 1962, 1963). Dos ejes principales de análisis de los ritos de rebelión, como el Carnaval desde la perspectiva antropológica, son las mismas polémicas de siempre—el materialismo marxista (con sus lentes que vean la desigualdad y el conflicto) y el funcionalismo (con su perspectiva de acomodación y adaptación, o bien la manutención del estado quo). Para poder decidir entre el materialismo y el funcionalismo, habría que analizar los efectos de la “rebelión.” ¿A cuál autoridad retan? ¿Permiten los ritos la consolidación de la identidad y la conservación del orden social (Gluckman 1963)? A caso la presentación de la identidad minimiza los conflictos a la vez que refuerza la identidad? O, como lo plantea Sheriff (1999) para Brasil, que el Carnaval en las barriadas pobres de la ciudad supera las divisiones de raza y de clase crea una identidad nacional. ¿Sería el caso aquí? ¿Cuáles son las desigualdades actuales en las comunidades—entre la gente con tierras, y sin tierras; los migrantes; los con más estudios, etc.? ¿Cómo se representan estas desigualdades—aparte del cobro de las cooperaciones—en las fiestas?

No me toca contestar estas preguntas, sin embargo, me parece que una respuesta fundada ayudaría a evaluar cuál de las dos perspectivas–la de la desigualdad y el conflicto o la de la identidad-adaptación–es más acertado. Tiendo a darle más peso al conflicto y la desigualdad en el análisis de la práctica de la cultura, pero reconozco que es complicado y dinámico y no poseo un conocimiento suficientemente profundo para poder llegar a una conclusión. De todos modos parece que las representaciones de Carnaval si tienen algo que ver con la identidad, con una resistencia quizá más étnica y regional que nacional. La rebelión contra la autoridad no llega a la puerta del Estado, pero quizá a las estructuras y poderes locales. Queda al autor, Eleuterio Xagaat García, contestar la pregunta, y no a mí: ¿El Carnaval refuerza o debilita la autoridad comunitaria?

Como extranjera, gente extraña, veo en las palabras (vienen gentes extrañas) una narrativa con fundamento histórico que puede remontar a las múltiples conquistas que han sufrido el pueblo chinanteco—desde la expansión mexicana y zapoteca en la sierra, a la conquista española, a la formación del estado-nación mexicana, a la extensión de la economía y cultura global, y finalmente, a la llegada más reciente de la gente extraña—los misioneros protestantes.

Cada una de estas conquistas, pero sobre todo la española, traía un holocausto demográfico. La historia de los nuevos asentamientos en las tierras bajas puede representar la recuperación demográfica que tardó unos siglos después de la conquista española (84). Pero todas las conquistas han traído muchos cambios: “han cambiado las cosas en Yolox” (66), como dice Vo.

En parte el análisis del autor es una narrativa sobre un pasado en el cual la cultura estaba intacta, un pasado donde se respetaban a los seres poderosos, a la vez que la narrativa conlleva una aceptación de la modernidad, es un lamento a no “perder nuestra cultura” como dice Vo (64), y un auguro de un presente y un futuro terrible, como cuenta Bito: “verás cuando lleguen monstruos que cagan un humo negro como el de la leña del pinabete” (66) (En el Siglo XIX, el ferrocarril de Oaxaca causó la deforestación casi total de la Sierra Norte para alimentar sus motores de vapor). Según las voces que capta Eleuterio Xaagat, han cambiado las cosas, y no por bien, aunque “la modernidad” parece tener sus atractivos. Estas narrativas históricas de un pasado bueno y un presente malo localicen a Yolox, Comaltepec y Temextitlán dentro de una especificidad histórico local, nacional, mesoamericano, y global. La contradicción entre esta narrativa y lo atractivo del mundo actual es casi universal, pero, en la fiesta de Carnaval en Temextitlán, que tuve la gran oportunidad de observar en 2017, presencié la síntesis de lo viejo y lo nuevo—a la vez que acatan a las formas antiguas y con contenidos antiguos, también parecen celebrar y apropiar la tecnología, el consumo y otras prácticas nuevas. Como todo rito, el Carnaval en estas comunidades en la Chinantla Alta, lleva sus etapas fijas, pero sus contenidos son dinámicos—con diferentes representaciones en las diferentes comunidades, y a lo largo del tiempo. En vez de provocar una añoranza por los tiempos perdidos, me emociona presenciar la creación, la apropiación, el dinamismo de estas culturas. Se están cambiando, pero no se están desapareciendo.

Como mujer, pregunto sobre el papel de las mujeres en las fiestas o bien, en la conversación sobre estas prácticas. Algunas de ellas me comentaron que no iban a la fiesta para evitar a los borrachos y a los chismes, mientras que las jóvenes resienten que no les dejan salir a bailar (76). No es de sorprender que haya conflicto generacional, pero me quedé con la duda, que a lo mejor no le toca a Eleuterio a resolver, de ¿que piensan las mujeres sobre Carnaval?

En suma, como antropóloga, como extranjera y como mujer, espero que mis comentarios se toman en el mejor sentido. Dejo mas preguntas que respuestas, ya que no me toca contestarlas, pero, a modo de conclusión, observo que todo rito es una representación, es una obra de teatro dirigido por los actores participantes. El rito, y las representaciones, son comentarios sobre la vida experimentada por la gente, y sus comentarios señalan que la vida ha cambiado y sigue cambiando. Y es lo alentador, lo mero bueno.

El trabajo de Eleuterio es único, innovador y bonito en que

- es un escrito desde la perspectiva desde adentro, de un participante pleno

- representa a las experiencias con imágenes más ricas que las palabras, aunque

- las palabras son increíblemente poéticas

- y, finalmente, crea un espacio para la representación—ahora y a futuro—del idioma, de las prácticas, y es más, de la cosmovisión dinámica de estas comunidades.

Adiós, adiós el cerro de Oaxaca

Adiós, adiós la villa de Guerrero

Que se lleva mi sombrero

Para nunca más volver (215)

pero me late que sí volverá…

=====

STRANGE FOLK ARE COMING

Vienen gentes extrañas… (strange people are coming) (6), coming to denounce the political and religious leaders of the communities of Comaltepec, Yolox y Temextitlán. This bilingual Chinantec-Spanish book describes Carnaval in these communities in the Chinantla Alta in Oaxaca, Mexico with the observations, participation, analysis and photography of the author, Eleuterio Xaagat García, between 2006 and 2010. The Chinantla Alta (map) is located almost at the top of the Sierra Madre Oriental, but the map, drawn by some of the strange folk who came–the Summer Institute of Linguistics—does not do justice to the high mountainous terrain of the region.

My comments reflect my position as an anthropologist, a foreigner and as a woman, but they pose more questions than answers, in the hope that of generating a longer conversation.

As an anthropologist, I see Carnaval as a ritual of rebellion, in which participants question authority, and create a space in which norms are broken (Gluckman 1962, 1963). Two main analytical axes that anthropologists use to analyze practices like rituals of rebellion such as Carnaval, are Marxist materialism (using the categories of inequality and conflict) and functionalism (using categories such as adaptation and status quo). In order to decide which best explains a practice, we need information about the effects of this so-called rebellion. What authority do they challenge? Does the ritual lead to the consolidation of identity and maintenance of the social order (Gluckman 1963)? If so, the representation of ethnic identity may smooth over conflict and permit peace to reign. More specifically, as Sheriff (1999) poses for Brazil, does Carnaval minimize racial and class differences in the creation of a national identity? What are the inequalities in these communities—between landed and landless, migrants, educated, or what? How are inequalities represented in Carnaval—aside from collecting family donations for the fiesta costs? I cannot answer these questions, but it seems that a substantiated answer would help decide which perspective—inequality/conflict or identity/stability—is the best explanation of events. Although I tend to give first and most weight to explanations that analyze conflict and inequality in cultural practices, I recognize that things are complex and dynamic, and furthermore, that I don’t know enough to come to a conclusion. At any rate, the representations in the Carnaval fiestas have something to do with identity, maybe about a resistance that is more ethnic and regional than national. These rebellions against authority certainly do not threaten the state, but they may shake local power structures.

As a foreigner in Mexico, as strange folk, I see in these words a narrative with a historical base that could go back through the many conquests the Chinantec people have suffered: as far as Mexica and Zapotec expansions into the sierra, or the founding of the Mexican nation-state, or to economic and cultural globalization, or to the arrival of the most recent strange folk, protestant missionaries.

Each of these conquests, but most of all the Spanish, brought demographic holocaust. The history of recent Chinantec settlements on the northern slopes of the sierra may represent, not just the development of hydropower, but also demographic recovery (84). But all conquests bring change: “things have changed in Yolox” as Vo says (66).

In one way, Eleuterio Xaaga’s analysis is a narrative about a good past with an intact culture, when people respected the powers that be, at the same time that it accepts modernity—a call to “keep our culture” as Vo says (64), and a prediction of a terrible present and future, as Bito says “you’ll see monsters shitting black smoke from burning firewood” (66). (In the nineteenth century, almost the entire northern Sierra of Oaxaca was deforested to feed the steam engines of the national rail system than ran through Oaxaca). According to the voices that Eleuterio captures, things have indeed changed, and not for better, in spite of the lure of modernity. These historical narratives—between a good past and a bad future—are virtually universal, but they locate Yolox, Comaltepec and Temextitlán within their own historical specificity in the general context of local, national, regional and global conquests and change. I observed some of these contradictions in fiesta of Carnaval when I visited Temextitlán 2017, a synthesis between old and new, both hewing to ancient forms and contents, and celebrating technology, consumption and new practices. Like all ritual, Carnaval is made up of fixed stages but with changing content, with differing representations in each the three communities, and over time. Instead of making me long for lost time, I was honored at being able to witness the creation, the appropriation, the dynamics of these cultures. Things are changing in the Chinantla Alta, but they are not disappearing.

As a woman, I have to query the role of women in these fiestas or in the conversation about cultural practices. Some women commented to me that they didn’t go down to the fiesta because of all the drunks and gossip, while young women resent that they aren’t allowed to go to the dance (76). While I’m not surprised to see generational conflict, I wonder what women think about Carnaval?

As an anthropologist, foreigner and a woman, I hope that my comments are taken as the questions of an ignorant extraña. I leave more questions than answers, but, by way of a conclusion, note that all rituals are representations or performances directed by the participants. They comment on current, not past, life and experience. In these cases, the participants in the fiestas of Carnaval in the Chinantla Alta of Oaxaca represent their histories and their lives as a struggle that is about authority, language, past and a changing present.

This work is unique, innovative and beautiful in that is written from inside, by a full participant; in that it represents experiences with images that are more eloquent than a thousand words; with words that are so incredibly poetic. Finally, this work creates a space for the representation, now and in the future, of the incredibly complex Chinantec language, practice and cosmology.

Goodbye, goodbye from the hills of Oaxaca

Goodbye, goodbye to the town of Guerrero

Take my hat

And never come back (215)

… but I bet they will.

FUENTES

Sheriff, Robin. 1999. “The Theft of Carnaval: National Spectacle and Racial Politics in Rio de Janiero” [https://culanth.org/articles/144-the-theft-of-carnaval-national-spectacle-and] (4feb18)

Gluckman, Max [http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Max_Gluckman] (4 feb2018).

Gluckman, Max. [1963] 2004. Order and rebellion in tribal Africa: Collected essays with an autobiographical introduction. Routledge. ISBN 0415329833

Gluckman, Max. 1962. Essays on the ritual of social relations. Manchester University Press.

Xaagat García, Eleuterio. 2016. Kolao´ Kiá Dzä Jmii. Juega enmascarado de Gente Idioma (El Carnaval de la Chinantla Alta). Oaxaca: México. Comisión Nacional para el Desarrollo de los Pueblos Indígenas, La Voz de la Sierra Juárez, el H. Ayuntamiento Constitucional, Santiago Comaltepec. ISBN: 978-607-8498-10-9).

With Don Martín, Tilcajete

With Don Martín, Tilcajete Sangre de Cristo maize

Sangre de Cristo maize

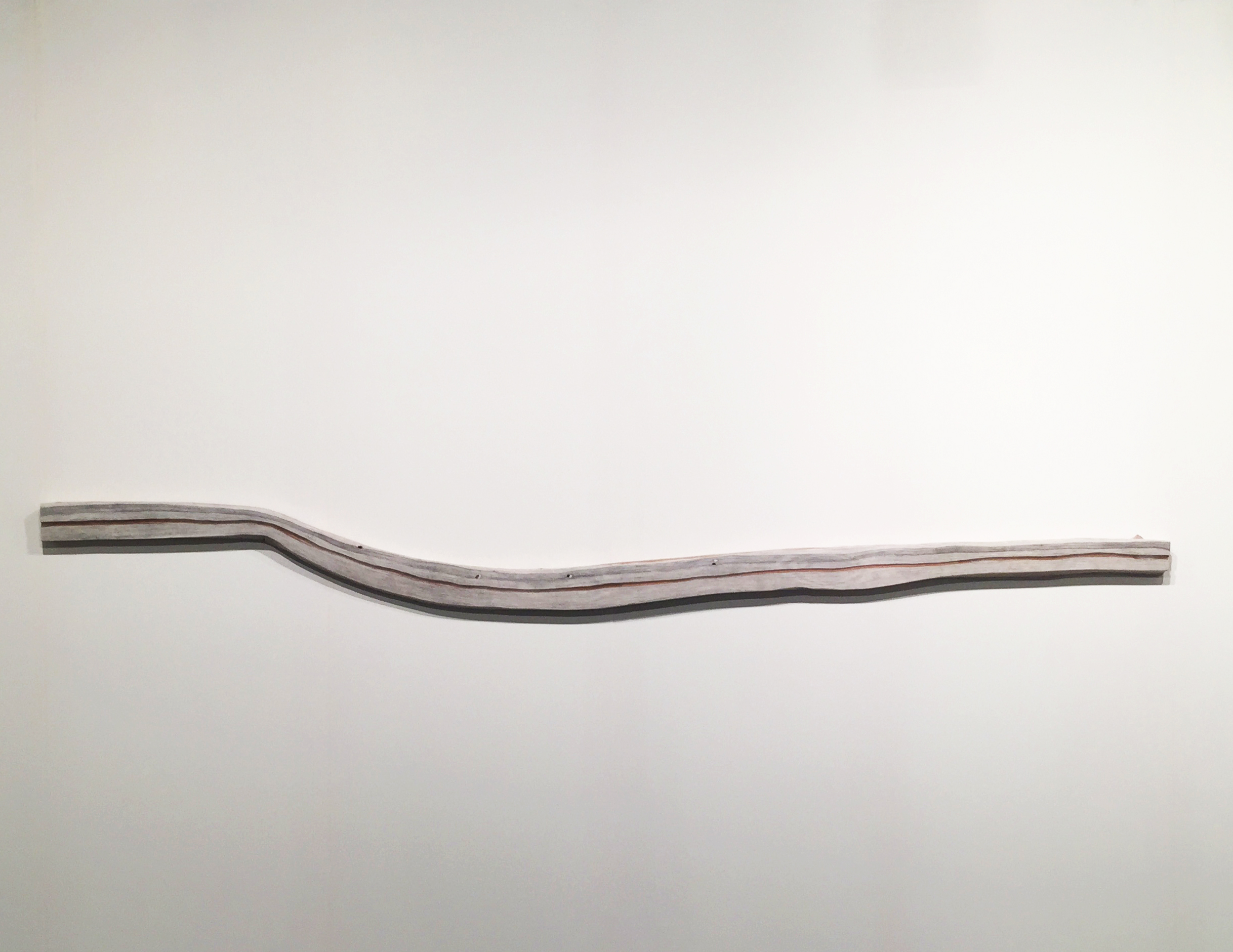

Vortex beneath the Vortex by Hu Xiaoyuan (Beijing Commune)

Vortex beneath the Vortex by Hu Xiaoyuan (Beijing Commune)

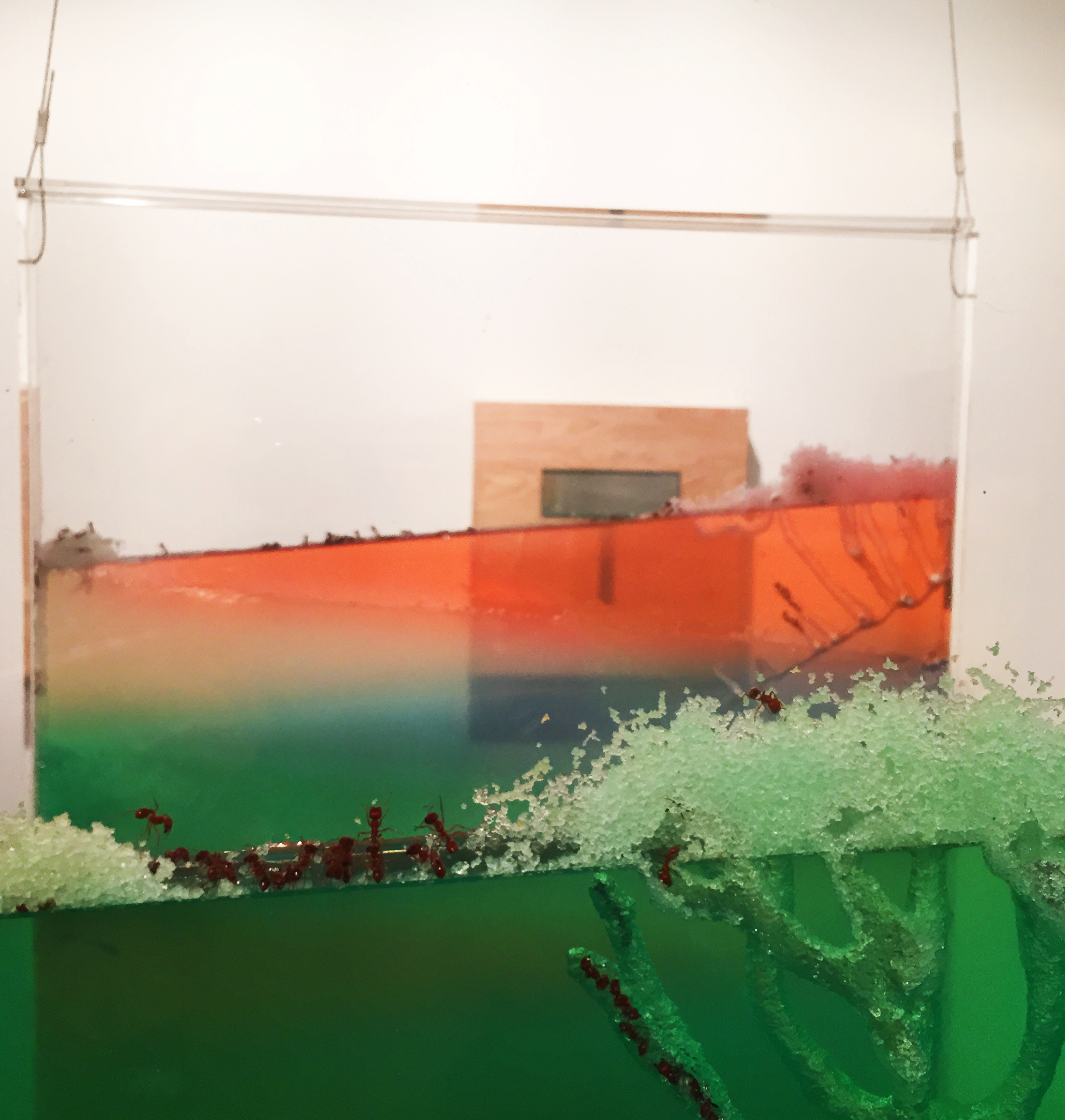

(Mujin-To Production, NADA)

(Mujin-To Production, NADA)

—probably the essence of the political art form.

—probably the essence of the political art form. (Kalfayan Galleries)

(Kalfayan Galleries)

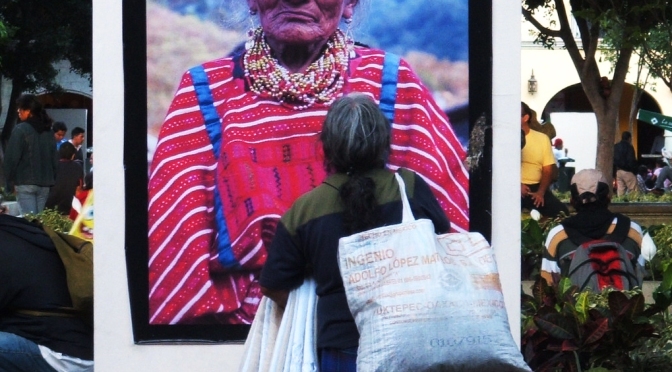

(Ginocchio Gallery, PINTA)

(Ginocchio Gallery, PINTA) Juan Ruiz Galeria (Miami, Venezeula)

Juan Ruiz Galeria (Miami, Venezeula) (Lulu Gallery, Mexico City, PINTA)

(Lulu Gallery, Mexico City, PINTA) (Labor Gallery, Mexico City, ArtBasel)

(Labor Gallery, Mexico City, ArtBasel) Mel Chin’s Cabinet of Craving (Miami Project) satisfying a craving for….?

Mel Chin’s Cabinet of Craving (Miami Project) satisfying a craving for….?

You must be logged in to post a comment.